Unlike other forms of energy poverty, hidden energy poverty refers to situations where households may not appear to be energy poor based on traditional indicators but are nonetheless struggling to meet their energy needs. These households remain invisible in local and national statistics because they are limiting their energy consumption and are unable to fulfill their desired level of comfort during winter or summer. This cost-saving behavior may cause households to fall just below the eligibility threshold for receiving support, such as winter fuel payments.

Although primarily focused on in scientific literature as a winter phenomenon, hidden energy poverty also affects households during summer heatwaves. In such instances, low-income households are forced to endure higher indoor temperatures for longer periods than those in the highest income group due to their inability to afford air conditioning or other cooling measures. Hence, this nuanced phenomenon requires a comprehensive understanding that transcends metrics and delves into the complex interplay of socio-economic, cultural, and regional factors.

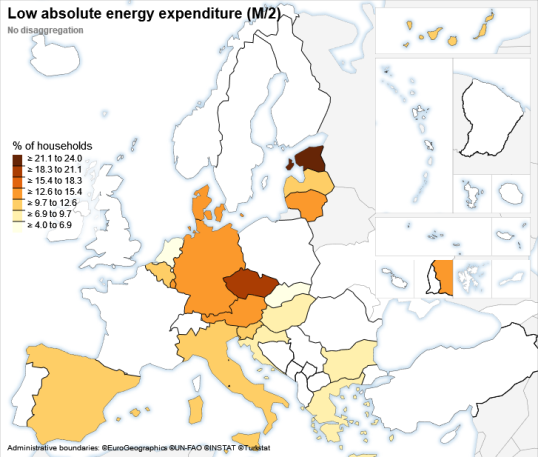

Accurately identifying and quantifying hidden energy poverty presents significant challenges. Current measurement tools typically rely on low absolute energy expenditures (M/2), capturing the economic dimension in each Member State, but fail to account for factors such as energy efficiency of the building, household conditions, and climate variability. The behaviors behind the statistical numbers are not always evident, as some households may self-disconnect, lack access to heating altogether, or accrue debt to cover energy costs. Moreover, income-based metrics may overlook household behaviors that also indicate energy poverty, such as low energy consumption or inability to meet energy needs.

While energy-restricting behaviors can be beneficial when voluntary and do not compromise basic energy needs, for vulnerable households, skimping on energy can have detrimental consequences on health and well-being. For instance, consider a family living in a poorly insulated apartment with limited access to affordable heating. To save on energy costs, they may keep their home at colder temperatures during winter, which could exacerbate mold and health issues. Colder indoor temperatures can trigger respiratory problems and increase the risk of asthma attacks, highlighting the intersectionality of energy poverty and health outcomes.

Alternative approaches, like checking how comfortable people feel with the temperature or measuring temperatures where people actually live show potential for spotting energy poverty that's not obvious at first glance. Moreover, hidden energy poverty manifests differently across European regions, necessitating localized interventions and policy adaptations. Examples from different countries show us just how varied this issue is and why we need strategies that fit each place's specific circumstances.

Lowest income groups struggle to cut back on energy use during crisis

The recent surge in inflation, coupled with a sharp increase in energy prices over the past two years, has exacerbated energy poverty among European households. According to a study by the Joint Research Centre, countries in the Baltics region, including Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, have experienced the highest increases in living costs, particularly energy prices. As a result, these countries are projected to have increased rates of hidden energy poverty due to inflation. Further research is needed to explore this issue thoroughly.

To grasp the full impact of the energy crisis on German households, the Expert Council for Consumer Affairs initiated a series of surveys called the "Energy Crisis Household Monitoring". Over two survey waves in 2023, they gathered data from nearly 4,500 households (four further waves of surveys are planned to be carried out). The findings underscore a concerning trend: energy poverty is becoming more prevalent in Germany. Particularly noteworthy is the disparity among income groups revealed by the survey. It highlights the significant challenges faced by the lowest income quintile in reducing their energy consumption compared to higher-income households during the crisis.

This can be due to the circumstance that high-income households find it easier to save energy by adapting their behavior without sacrificing comfort, for example due to the fact that they live on average in a relatively large living space. If there is a separate and rarely used room in such a household, energy consumption can be reduced effectively and without loss of comfort by not heating this room.

Low-income households, on the other hand, are more likely to rent in Germany and are therefore unable to decide on their type of heating. In addition, rental apartments are, on average, in a worse energy-efficient condition. In addition, rental apartments are more often heated with energy sources that have experienced particularly high price increases during the energy crisis. This applies in particular to natural gas, district heating and heating oil. In the panel survey, low-income households stated that they made above-average efforts to save energy. However, during this crisis, they estimate the realised energy-saving potential through behavioral adjustments to be lower compared to high-income households. Overall, the data suggests the following explanatory pattern for the different increases in energy costs across income groups: Lower income groups live more often in poorly insulated rental apartments and heat more often with energy sources that have experienced higher price increases during the energy crisis. This highlights systemic inequalities in housing conditions and energy access.

Elaborating a survey to supplement non-available data

In response to these challenges, on the ground, a combined approach is essential for local governments to effectively evaluate the current level of energy poverty from economic, consumption, and behavioral perspectives. By considering behavior patterns alongside spending patterns, policymakers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of households in need of renovation or energy assistance. This holistic approach enables targeted interventions that address the root causes of energy poverty and promote sustainable solutions. Another possibility to detect hidden energy needs and better target support measures is to integrate data from smart sensors or smart meters.

In EPAH's technical assistance in Sátoraljaújhely, Hungary, the objective is to elaborate a detailed diagnosis of energy poverty to develop proper pathways for the implementation of energy poverty measures. The expert Zsuzsanna Koritar from Habitat for Humanity Hungary explains that they decided to focus on the development of a questionnaire to collect additional information that cannot be assessed using official national datasets and EU statistics. The expert explains “we collected and analysed the latest census and household budget survey, the central database of energy performance certificates for buildings and other national databases of the Central Statistical Office but realized that an important aspect was missing: the energy use characteristics and attitudes and behaviours that influence energy consumption.“ Based on the analysis results the idea is to establish a working group, which will be tasked with making recommendations to municipal decision-makers on future measures to alleviate energy poverty based also on behavioural aspects.

Details

- Publication date

- 5 April 2024

- Author

- Directorate-General for Energy